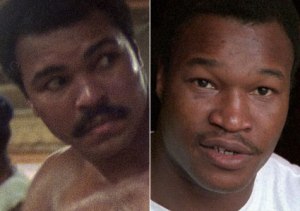

Larry Holmes may have been the least (and most) obvious Albert Maysles subject to walk the face of the earth. A brilliant boxing technician who offered the sporting public nothing but his skills, he was a villain in the delicate racial atmosphere that was 80’s sports media. Blunt, prideful, and with no bullshit barometer, he was an easy target for Reagan era sensibilities, going against the need people had for every black athlete to be a moderate actor. It didn’t matter that he committed no crime and showed no truly deplorable outward behavior, Holmes was considered evil because he wasn’t appropriately charming. If not as galvanizing and charismatic a symbol as Muhammad Ali(Holmes’ predecessor as heavyweight champ and the most culturally important athlete in the history of this planet and) Larry was a symbol in his own right, an every-Blackman who just wanted to do his job and was punished for being human.

In a different yet similar way in which he cuts through the preconceived notions people had of Salesmen (Salesmen), an “eccentric” mother and daughter (Grey Gardens), and the Rolling Stones (Gimmie Shelter), Maysles goes through the stereotypes of Black Athletes In Muhammad and Larry, and the result is a moving work that is as much about race, celebrity, family, and sorrow as it is about boxing. Using the juxtaposed footage of both Holmes and Ali’s training camps, Maysles uses his direct Cinema Technique to let the fighters, their camp members, and sportswriters provide a complex subtext. It is a story in which one can be struck by the humanity its protagonist show. In the end, however, it is a tragedy, possibly the most harrowing one in all of sports, where a good man had to turn a great man into a living corpse, and knew( along with many of the people in the film) he was going to do it for months in advance.

In Muhammad and Larry, Holmes’ words might not be Madison Avenue ready but his actions warm the heart to its cockles. Through out the film Holmes doesn’t give off a single inkling that he had the most elite title in all of sports. He wears a non descript T-Shirt and jeans. He talks of his wife more than he talks of money. He pays more attention to his child more than his properties. The background doesn’t make a case for Holmes; it makes a case against anyone who would think him a bad man. If Holmes was white, he’d be considered a Norman Rockwell hero come to life. But because he was a black man, he was considered by much of the country to be a moody, too proud nigger.

He was also considered, by the rest of the county, to be the man who followed “The Greatest”. Ali, the other protagonist in Muhammad and Larry, comes as advertised. Evolving from some of the too sharp racial edges he had in his youth, Muhammad conducts his camp like the most authentically joyful carnival one will ever see. At his best, Ali’s cultural brashness and sweetness meld to something irresistible for the viewer and the members of his entourage. Throughout the film, he engages in card tricks, hangs out with old friends and charms the hell out of anyone who came to his Deer Lake Training Camp. Possibly the most poignant moment was when-out of the blue-he has a tickle fight with his old business partner and, after being told that Holmes likes him, says “ well I like him too” with the sweetness of a 12 year old kid.

And throughout all the humanity of this movie, the horror of what was going and eventually did happen lurked in every loop. For all the times Ali could make you smile in this movie, he could not make you forget that-because of so many brutal fights he had- he was talking at half his mental capacity. The people in his camp talk lovingly about him, but their voices tell you they know he doesn’t have a chance in hell, that when they are speaking of him they are talking in elegiac terms. As brusque as he could be, Holmes is almost apologetic toward Ali, having to psyche himself up but knowing too well of the former champions declining health. In clips present and past, he is cantankerous about the fight but wistful toward the man who first gave him a chance in boxing (as a sparring partner) and the man that-sadly-he had to brutally beat.

Dear god, he did. The tragedy of that fight wasn’t that Ali was a shell of his former greatness. It was that the fight completely took his physical mind away. The thing that certified his greatness as a fighter-his toughness and will to take an inhuman amount of punishment-was the thing that eroded his beautiful cognitive skills. He took 400 punches (in 14 rounds) against Joe Frazier in their third fight, 300 (in 15 rounds) against Ken Norton in their third fight and 300(in 15 rounds) in his fight with Ernie Shavers the following year. After every one of those battles (and two tough scraps against Leon Spinks in 1978) it was obvious that there was less and less of him, so much so that people were as terrified for his fight with Holmes as they were for a sleeping man in front of an oncoming train.

On October 2, 1980 he took 300 punches from that train in the span of 10 rounds. He was supposed to earn 8 million dollars from it, but Don King stole a million of it in a paperwork hustle. Herbert Muhammad, the man who drained his money because he was bitter that Ali left his father’s NOI sect for a more progressive school of Islam, took a good deal of the rest. Holmes, who earned 2.5 million dollars for fight, was touched with less than 20 punches. After his victory, as a visibly shaken Howard Cosell was interviewing him, he wept like a child. After the fight, Ali never spoke in coherent paragraphs again.

In the end, Muhammad and Larry asks what any great art that has his subtext as a commentary for life asks; “Can you throw away any of this away? Can you look away from any of this”? Without Muhammad Ali, you wouldn’t have Richard Sherman, Barack Obama, or the swagger of any progressive black person in the last 50 years. A married man for 40 years and stalwart in the Easton community, Larry Holmes could teach a great deal of America how to live a decent life. All of this can’t take away that Muhammad made his way in a sport that brutalized him beyond the imagination. Everything wonderful and horrible about boxing and life is in Muhammad and Larry. Like the skill and heart of its subjects, the movie is something you can’t pin, pigeonhole, or explain away. One cannot say anything other than to acknowledge that it’s art: haunting, sometimes very beautiful, and sometimes very, very tragic.

Beautifully written piece, a good fit to the film you write about.